The Book of Bamidbar is also called by the rabbis “Chumash HaPekudim,” (loosely) the Book of Numbers, since it contains two lengthy censuses of Bnei Yisrael. Counting people is sometimes viewed positively in Tanach, while other times it is considered a sin. Why is there such a varied view of counting people in Jewish sources?

Bamidbar opens with God commanding Moshe to count the males who are of age to be soldiers, in preparation for entering the land of Israel. Rashi comments: “Because of God’s love for Israel, He counts them often…” This is in contrast to when King David counts the people. The book of Divrei Hayamim states that God was displeased with this counting. What was the difference?

In Bamidbar God commands the counting, whereas later, David counted from his own initiative. Moreover, Sforno explains that in Bamidbar they were counted “with names,” highlighting each individual for their unique contribution to the nation. Thinking of people as numbers is dangerous, as we know too well from Jewish history. One last interpretation: Ramban notes that there is a significant difference in language between Bamidbar and Divrei Hayamim. In Bamidbar, the word used for counting is from the root פקד, which can also mean redemption. In the David narrative it is ספר, which only means to count. Ramban explains that counting should be done rarely and only when necessary, for positive, redemptive purposes. David’s counting was not for any good reason.

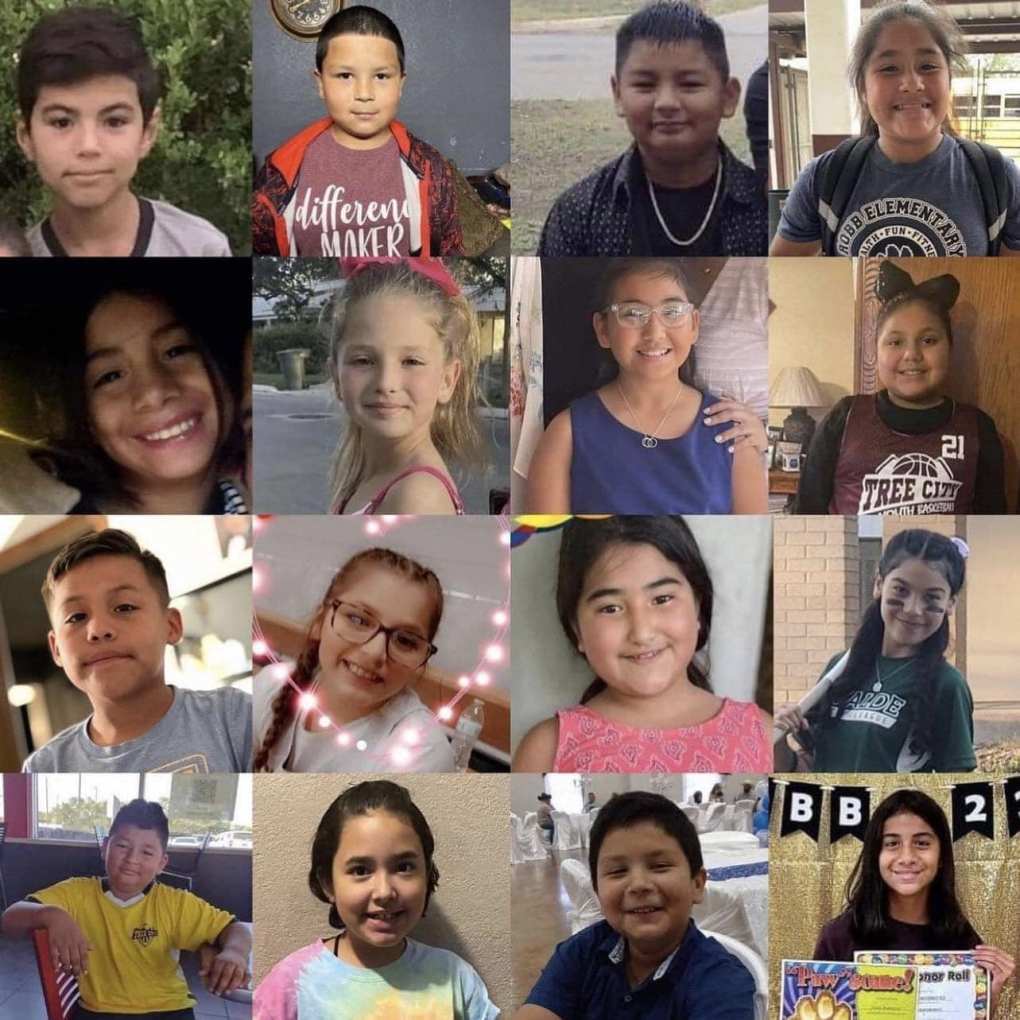

Unfortunately, this is a particularly relevant message, as we try to process the news of so many young lives lost this past week. The parsha is a reminder that each one has a name and is an entire world. May our countings be only for redemptive purposes. Shabbat Shalom and Yom Yerushalayim sameach -Karen Miller Jackson