“With great power comes great responsibility.” In Parshat Shoftim, societal leaders—whether judges, prophets, sages, or kings—are commanded to pursue justice and adhere to a strict code of ethical behavior. However, there are times when every individual is called upon to engage in introspection and take responsibility for the welfare of society as well.

Devarim 21 describes the mysterious ceremony, done in biblical times, of “eglah arufah.” When a murder victim is discovered outside a city and the identity of the killer is unknown, the elders of the closest city take an unworked heifer and break its neck. Then there is a two-part tikkun. First, the leaders are called upon to take responsibility, which consists of a declaration: “Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done,” and then a prayer to God: “Absolve Your people Israel whom You redeemed…”

What is the purpose of the leaders declaring “our hands did not shed this blood”? Rashi, citing midrash Sifrei asks, “do we really think the elders are murderers?” Rather, they mean that they never encountered this victim, and they did not leave a vulnerable person without help. This ritual underscores the value the Torah places on each and every life and the heavy responsibility on leaders to protect their people. Why, then, do they pray that God absolves all of Israel and not just themselves? When an innocent life is taken and justice is not served, the moral deficiency can reverberate in the nearby city and throughout all of Israel. So all of Israel must pause and reflect on what has occurred. This is why the tefillah seeks redemption for the entire nation.

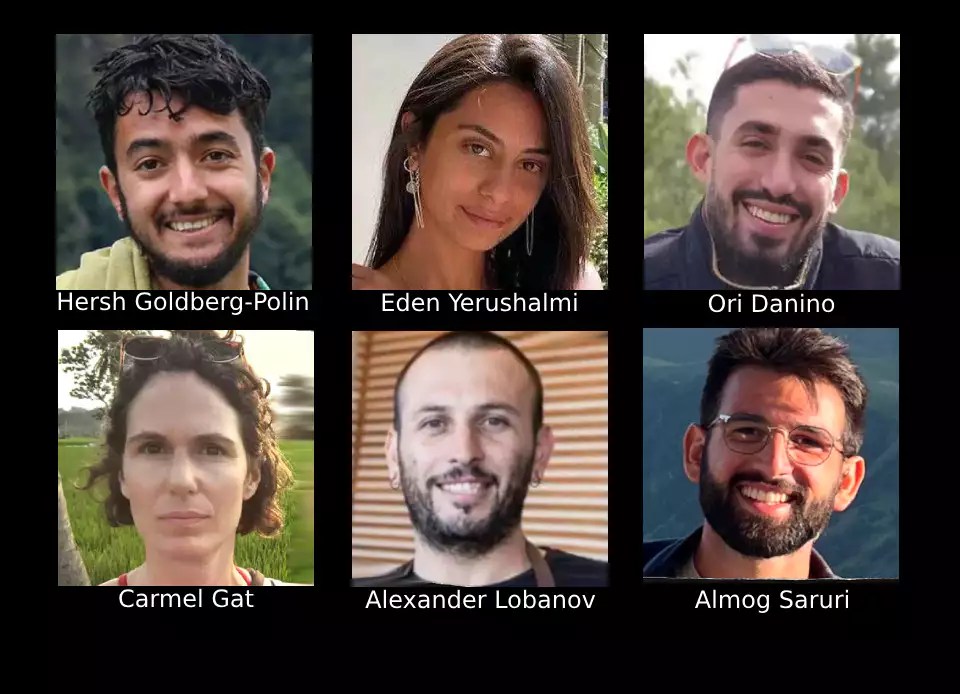

The eglah arufah is no longer practiced, but its core ideas remain relevant—especially this week. May the memories of Alexander, Almog, Carmel, Eden, Hersh, and Ori be a source of societal healing and redemption in our time. Shabbat Shalom -Karen Miller Jackson